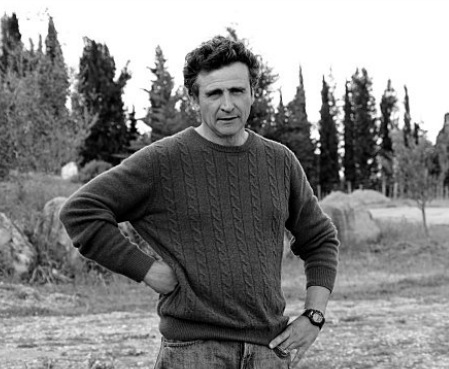

Giuseppe Liberatore is the Director of the Consortium of Chianti Classico wine

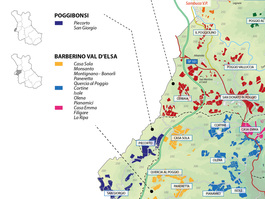

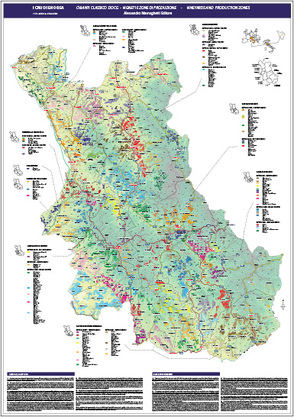

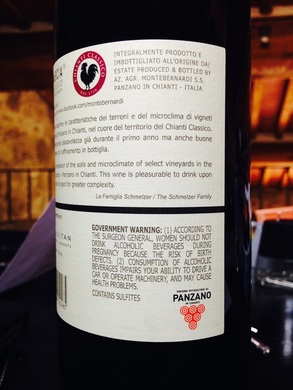

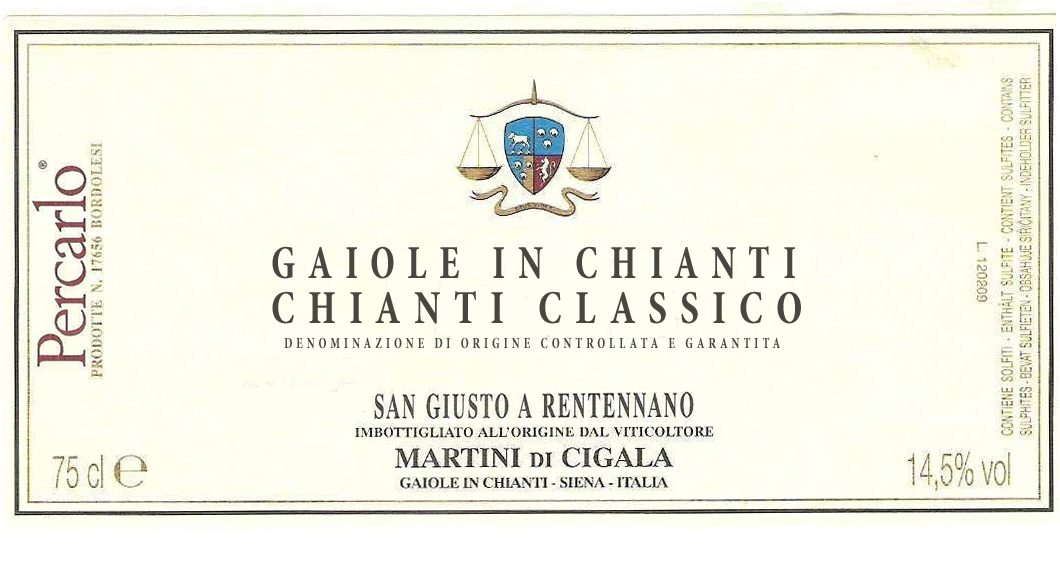

Liberatore explains that “in a territory like ours, there are all the elements to do it; some might coincide with town borders, others might be zones within a township which, for history, tradition, and notoriety (Panzano and Lamole, for example… but there are many more) have their own identity”.

“Comparison and common sense,” he concludes, “will help us find the best solution; the time is right. Meetings about the territory will begin soon. The president and director have already been appointed by the Cda”.

extracted from interview on wechianti.com, Matteo Pucci

Liberatore explains that “in a territory like ours, there are all the elements to do it; some might coincide with town borders, others might be zones within a township which, for history, tradition, and notoriety (Panzano and Lamole, for example… but there are many more) have their own identity”.

“Comparison and common sense,” he concludes, “will help us find the best solution; the time is right. Meetings about the territory will begin soon. The president and director have already been appointed by the Cda”.

extracted from interview on wechianti.com, Matteo Pucci

Una porta aperta - Giuseppe Liberatore discute la possibilità di zonazione nel futuro di Chianti Classico

il direttore del Consorzio Vino Chianti Classico, Giuseppe Liberatore

Liberatore spiega che “in un territorio come il nostro ci sono tutti gli elementi per farlo. Alcune possono coincidere con i confini dei comuni, altre possono essere delle zone all’interno di un comune che per storia, tradizione, notorietà (Panzano, Lamole, ma ve ne sono molte altre) hanno una identità propria”.

“Il confronto e il buon senso – conclude – ci aiuteranno a trovare la soluzione migliore: i tempi sono maturi, presto partiranno gli incontri sul territorio, presidente e direttore sono già stati incaricati dal Cda”.

estrazione dal articolo wechianti.com, Matteo Pucci

Liberatore spiega che “in un territorio come il nostro ci sono tutti gli elementi per farlo. Alcune possono coincidere con i confini dei comuni, altre possono essere delle zone all’interno di un comune che per storia, tradizione, notorietà (Panzano, Lamole, ma ve ne sono molte altre) hanno una identità propria”.

“Il confronto e il buon senso – conclude – ci aiuteranno a trovare la soluzione migliore: i tempi sono maturi, presto partiranno gli incontri sul territorio, presidente e direttore sono già stati incaricati dal Cda”.

estrazione dal articolo wechianti.com, Matteo Pucci

RSS Feed

RSS Feed